Joseph Stalin has the status of martyr on this timeline; his convenient death in the Battle of Moscow made up for a multitude of previous sins, at least in the realm of public opinion. His reputation certainly overshadows that of his successor, Vyacheslav Molotov: while Molotov was able to wage the Great Patriotic War competently enough, he was ironically much less able to achieve Soviet postwar diplomatic goals on his own authority than he was as the agent of another’s will. The end result is a Central Europe that is a quiet, yet very real, Cold War battleground – one not helped by internal rumblings against Molotov’s continuing rule…

Joseph Stalin has the status of martyr on this timeline; his convenient death in the Battle of Moscow made up for a multitude of previous sins, at least in the realm of public opinion. His reputation certainly overshadows that of his successor, Vyacheslav Molotov: while Molotov was able to wage the Great Patriotic War competently enough, he was ironically much less able to achieve Soviet postwar diplomatic goals on his own authority than he was as the agent of another’s will. The end result is a Central Europe that is a quiet, yet very real, Cold War battleground – one not helped by internal rumblings against Molotov’s continuing rule…

Molotov, 1956

Current Affairs

A superficially milder Cold War in Europe threatens to turn hot from Soviet internal tensions.

Divergence Point

1941: Joseph Stalin felled by a bullet during the Battle of Moscow. Vyacheslav Molotov succeeds him, then spends the next five years dealing with the resultant power struggle.

Major Civilizations

Western (Empire with rivals)

Great Powers

People’s Republic of China (dictatorship, increasingly feudal, CR2-6), Republic of France (representative democracy, CR4), United Kingdom (representative democracy, CR4), United States of America (representative democracy, CR3), Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (dictatorship, CR5)

Worldline Data

TL: 7

Quantum: 7

Mana Level: low

Centrum Zone: Orange

Infinity Level: P5

It is still unclear which action during the Battle of Smolensk was the triggering action that permitted the Wehrmacht to advance to the actual outskirts of Moscow (as in, one-half mile from Red Square) during the Battle of Moscow; in fact, it is only assumed that the divergence point took place during that first battle. However it occurred, the attackers were well within even short artillery range – and were able to kill Joseph Stalin at some point during the fighting. The “official” date of December 7, 1941 is widely believed to be an attempt at propaganda, although it is admitted that the heaviest artillery attacks took place during that time period. Naturally, the Soviets did not announce the death of the Man of Steel until the next spring, well after Vyacheslav Molotov’s taking and first consolidation of power. The new General Secretary did about as well as Stalin did in Homeline; while Molotov was ready to give the armed forces a freer hand, he faced considerably more in the way of long-term dissent than did his predecessor, leaving to a rough balance on the military front.

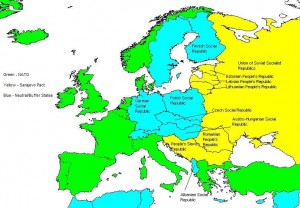

This unsteadiness at home cost him and his country somewhat when it came to negotiations with the other Allies. While the Tehran Conference (December 1943) achieved most of the USSR’s goals, the ones at Tangiers (February 1945) and Potsdam (August 1945) were less satisfactory. The Polish Government-in-Exile was confirmed as the legitimate government of Poland, and the United States and United Kingdoms were able to insist that Czechoslovakia, Austria, and Hungary (the latter two later recombined) be subject to free elections. The Soviet Union was given a free hand in the Balkan and Baltic states, as well as being confirmed in their right to have what would turn out to be significant influence in the above countries, plus Finland and Germany. The postwar map was thus somewhat different than Homeline’s: while Germany reunited in 1951, it, Poland, Finland, Czechoslovakia, Albania, and Austria-Hungary (also reunited in 1951, to the pleasure of neither country) had become “social republics:” popularly-elected governments with strong (and Russian-subsidized) Marxist minority (in Albania’s case, majority) parties, an initial emphasis on agricultural production over manufacturing, and almost no militaries worth naming. The Balkan states were amalgamated into an outright Marxist People’s Slavic Republic: they, along with the Romanians and Baltic states, became part of the Soviet-dominated Sarajevo Pact ostensibly placed in opposition to America/Great Britain’s NATO. The Marshall Plan still existed in this timeline, but notably skipped over the Social Republics, due to Russian worries about German reunification making the entire question diplomatically awkward.

Molotov’s Central Europe in 1956 is increasingly a hotbed for espionage. While weak militarily, and noticeably less developed than their neighbors to the West, the relatively open economies of the Social Republics have allowed them some recovery. The escalating Cold War has led both NATO and the Sarajevo Pact to encourage industrial and financial development; there is quite a lot of potential money to be made in Germany or Czechoslovakia these days, by both private individuals and governments. The touchy political situation encourages small-scale operations by intelligence agencies; absent an actual NATO/Pact border, there’s less perceived need for large scale militaries on the continent, and the recent acquisition of atomic weapons by the Soviet Union has made a conquest of Central Europe suddenly fraught with worry for both sides. Active, deniable spying is thus seen as both safer, and more cost-effective. Elsewhere in the world, African and Asian Communist movements are somewhat less advanced, due to the focus on Europe; the PRC in particular is still engaged in an internal civil war that began when Mao Tse-tung died in 1953. Rumors that the Molotov government had the dictator assassinated are both widespread and true.

Throughout it all, Molotov has stayed in increasingly tenuous control, both helped and hampered by the fact that various elements of the Soviet government have discovered that the current situation allows to them a certain amount of personal enrichment. Although these sorts of things are strictly forbidden to good Marxists, there is a growing current of dissatisfaction (being very carefully led by Nikita Khrushchev) with the Molotov government over what is increasingly being seen as bad postwar decisions in foreign policy. In part to counter this, the Molotov government has been pushing for an expansion of Soviet influence in Europe, with an eye to bringing first the Social Republics, then Italy and Greece, into the Pact. The problem, of course, is that the Social Republics know that a request for military aid will be favorably received by the NATO countries, and have become increasingly expert in playing both sides off of the middle. The Austro-Hungarians in particular are fairly eager to wriggle out of the geopolitical trap that they have found themselves in, and are showing signs of preparing to force the issue…

Outworld Involvement

Molotov, being a Quantum 7 timeline, is of course in Centrum’s backyard; Infinity suspects that it and Homeline both discovered it at roughly the same time, which means that the I-Cops actually have a bit of an advantage. While Interworld can field English-speaking agents easily enough, the world is still sufficiently similar to Homeline’s history that it’s easier for Infinity’s agents to both run operations, and detect the anomalies that might suggest Centran interventions. If Infinity can keep Centrum from getting a foothold, the theory goes, Centrum will continue to waste a disproportionate amount of effort on trying to take control the timeline. Whether this theory holds water or not is a subject for quite a few debates, but many Homeline corporations are finding Molotov to be profitable despite its relative distance: the focus on Europe by both power blocs is such that industrial operations in South America or East Asia can be quietly taken over and their end products redirected without anybody noticing. Regular tourism is under-developed, although book tours are actually fairly common: the spy genre is quite popular on Molotov, from Robert Heinlein’s blockbuster techno-thrillers to Gregory Corso’s poetic retellings of Jacques Lien, suave yet brutal agent of Unione Corse.

The material presented here is my original creation, intended for use with the In Nomine and GURPS systems from Steve Jackson Games. This material is not official and is not endorsed by Steve Jackson Games.

In Nomine and GURPS are registered trademarks of Steve Jackson Games, and the art here is copyrighted by Steve Jackson Games. All rights are reserved by SJ Games. This material is used here in accordance with the SJ Games online policy.